Inflation shock may push the RBI to hike rates in June

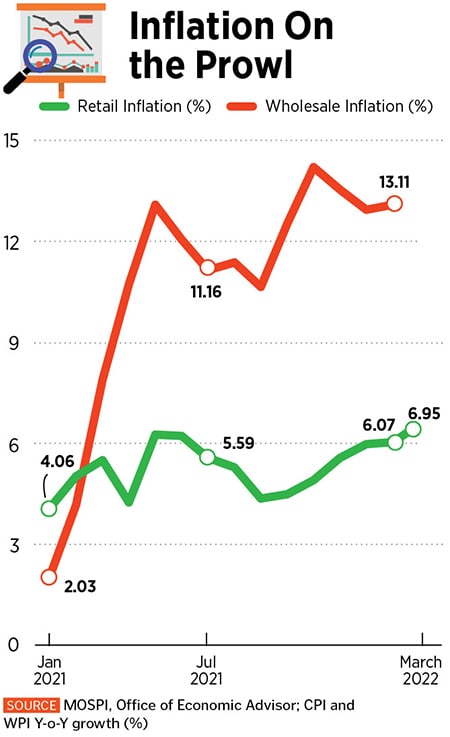

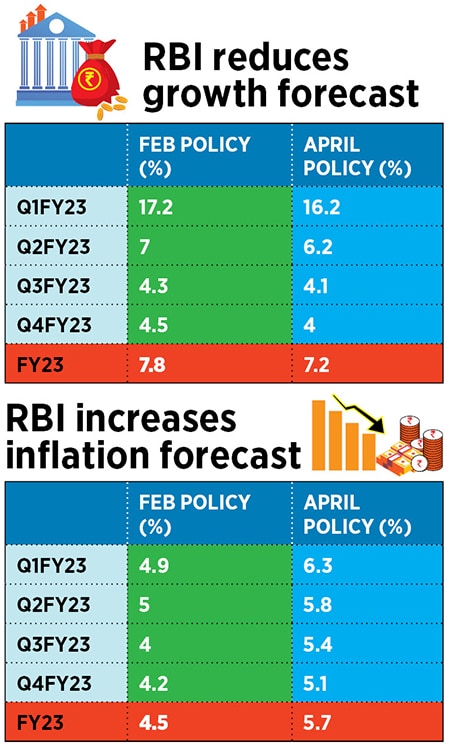

Inflation hit 6.95 percent in March, leading to concerns that retail inflation may breach the upper limit of the RBI's 2-6 percent target band for three successive quarters now, even as the economy struggles with growth challenges

Indrani Majumder, a consumer, buys vegetables from a roadside vegetable vendor in Kolkata, India, March 22, 2022. Picture taken March 22, 2022; Image: Rupak De Chowdhuri / REUTERS

Indrani Majumder, a consumer, buys vegetables from a roadside vegetable vendor in Kolkata, India, March 22, 2022. Picture taken March 22, 2022; Image: Rupak De Chowdhuri / REUTERS

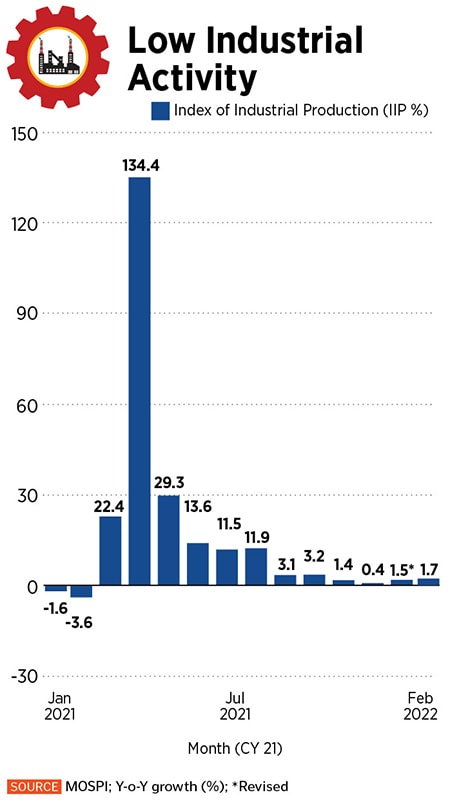

Barely three days after the monetary policy committee’s long-drawn decision to prioritise rising inflation over weak growth by gradually weaning the economy off ultra-accommodation, the economy was in for a double shock.

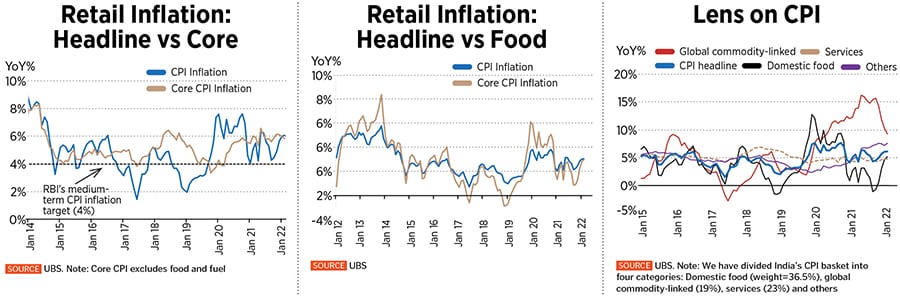

One, the consumer price index surged to 6.95 percent from 6.07 percent in February, much higher than economists’ and analysts’ estimate of 6.3-6.4 percent. Clearly, as feared for long by leading economists, inflation is no longer transient.

The rise in food prices mainly drove up retail inflation, suggesting that the pass through of high commodity prices had begun. Core inflation (excluding food and fuel) also rose sharply by 60 basis points to 6.6 percent. Moreover, rural core inflation increased to 7.7 percent while urban core inflation stood at 5.7 percent. According to economists, core inflation is likely to remain sticky and elevated in the coming months.

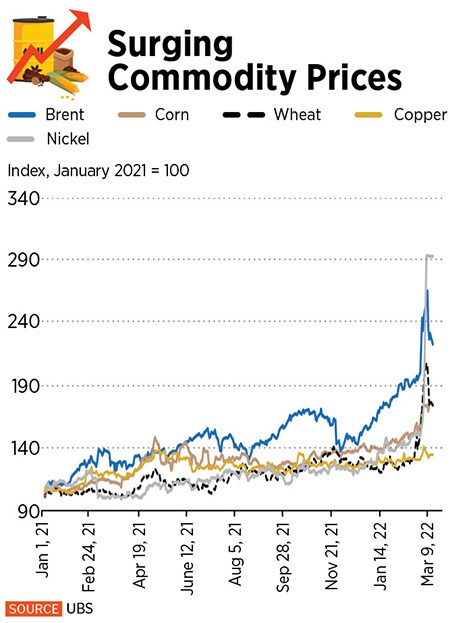

In turn, price pressures are expected to continue to increase in the coming weeks. Fuel prices, specifically petrol and diesel, are up by 3-4 percent in April in comparison to the previous month. Edible oil and gold prices are inching upwards and will continue to weigh on retail inflation.

In turn, price pressures are expected to continue to increase in the coming weeks. Fuel prices, specifically petrol and diesel, are up by 3-4 percent in April in comparison to the previous month. Edible oil and gold prices are inching upwards and will continue to weigh on retail inflation.

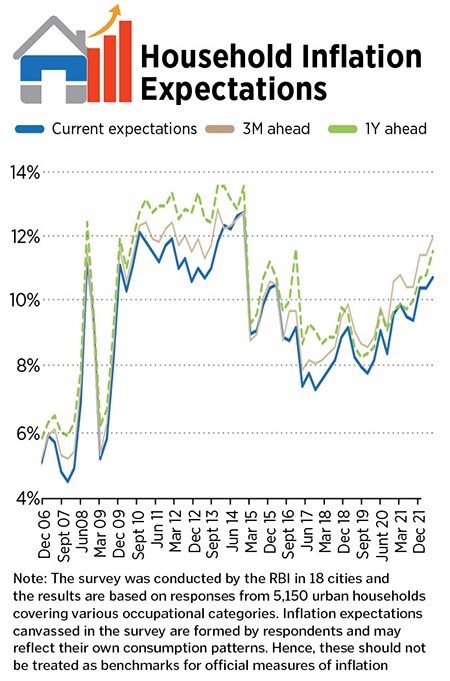

“Unfavourable base effects in case of other food items are expected to push headline CPI inflation further up to 7.3 percent in April,” said Bank of America’s (BoFA) economists in a report dated April 12. The brokerage has sharply revised its CPI inflation estimate for FY23 upwards to 6 percent versus 5.5 percent earlier. This is higher than the RBI’s inflation forecast of 5.7 percent.