RBI monetary policy: Too much at stake

In the backdrop of rising inflation and global central banks' liquidity tightening, calls for the RBI to act similarly and start raising interest rates have grown. Meanwhile, India's pace of growth post-pandemic remains patchy. All these, and an aggressive government borrowing programme have raised bond market concerns further

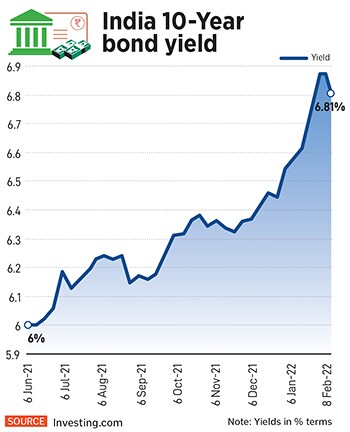

India’s 10-Year bond yields have been climbing relentlessly. They are close to their higher levels since July 2019

India’s 10-Year bond yields have been climbing relentlessly. They are close to their higher levels since July 2019

Image: Shutterstock

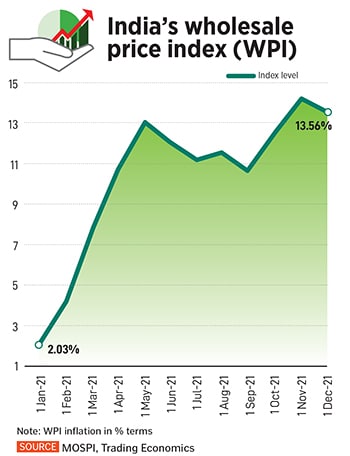

The upcoming Reserve Bank of India (RBI) monetary policy meeting, scheduled to be announced on February 10, has assumed significance due to a range of economic issues which need to be resolved. India’s wholesale price-based inflation is in double digits since April 2021 and needs taming, even as the governor Shaktikanta Das says the bank has remained ‘accommodative’ in its policy stance in an attempt to revive and sustain growth, as India rides out of the impact of the pandemic.

But, on the other side, India’s 10-Year bond yields have been climbing relentlessly. They are close to their higher levels since July 2019 (see chart), spooked by the global tightening of liquidity from central banks, increasing inflationary concerns and a rise in the government’s own borrowing programme, as announced in the FY23 budget. Higher bond yields not only put pressure on interest rates, but also lead to a rise in lending rates.

Das will be keenly heard by the market on inflation, trajectory of rates for 2022, the stance of the bank relating to growth and the message to the bond market. The market will also want to hear the RBI’s commentary in a scenario when several central banks have started to embark on tightening of liquidity measures.

The US Federal Reserve in January-end said it will raise interest rates soon for the first time in three years. The Bank of England, this month, hiked rates for the second time in three months and the European Central Bank has abandoned its stance of not raising rates in 2022, while recognising inflation risks. “Global tightening of liquidity, the US Fed turning hawkish, the rise in inflationary concerns across economies and the increase in the government borrowing are the reasons for the rise in yields,” says Devang Shah, co-head, fixed income at Axis Mutual Fund.

Nomura India’s Business Resumption Index rose to 113.2 for the week ending February 6, from 104.8 levels the week earlier, indicating 13.2 percentage points over the pre-pandemic level. All critical elements such as mobility, the labour participation rate and demand for power, rose week on week. “The improvement is indicative of the ebbing third wave and lower public risk perception…” analysts Sonal Varma and Aurodeep Nandi said in the note to clients.

Nomura India’s Business Resumption Index rose to 113.2 for the week ending February 6, from 104.8 levels the week earlier, indicating 13.2 percentage points over the pre-pandemic level. All critical elements such as mobility, the labour participation rate and demand for power, rose week on week. “The improvement is indicative of the ebbing third wave and lower public risk perception…” analysts Sonal Varma and Aurodeep Nandi said in the note to clients. In a separate development, India expects to be included in the global bond indices, a move which Morgan Stanley Research had said was “imminent” in a report last October. If this inclusion takes place, it might attract more than $170 billion in bond inflows into India in the next decade and lower borrowing costs. The report expected India to be included in two out of the three major global bond indices in “early 2022”, its chief India economist Upasana Chachra had said.

In a separate development, India expects to be included in the global bond indices, a move which Morgan Stanley Research had said was “imminent” in a report last October. If this inclusion takes place, it might attract more than $170 billion in bond inflows into India in the next decade and lower borrowing costs. The report expected India to be included in two out of the three major global bond indices in “early 2022”, its chief India economist Upasana Chachra had said.